The Life and Times of Frank Watts

Frank Watts reminisces about his days playing football, powerlifting, and meeting the love of his life.

Words by Terrell Manasco | Images by Al Blanton and courtesy Frank Watts

Dressed in a Hawaiian shirt, khaki shorts, sandals, and a tan baseball cap with an American flag on the front, Frank Watts sits at his dining room table, sifting through a series of old sepia-tinted photos and newspaper clippings. In a thundering voice that frequently dips into a near-croak, Watts guides us on a tour backward in time, balancing his narrative with interesting anecdotes and praise for his two great loves: his wife, Pinkie, whom he affectionately calls “that redheaded woman,” and Jesus Christ.

“I'm a Christian. That's my number one priority—Jesus Christ,” Frank says. “He's numero uno.”

Born in 1948, Marion Frank Watts was the son of Frank and June Watts. The family lived in Jasper and survived on his father’s meager salary as a teacher and principal. When Frank was eight months old, his family moved to Florence in a 1938 Ford with chicken wire strung over its missing passenger window.

“My bassinet was a dynamite box in the floorboard,” he says.

Five years later, they moved back home, raising pigs and chickens on a small farm near Cordova.

Watts was taught to work from a young age. Later, he mowed grass and hawked GRIT newspapers and soft drink bottles for a few cents.

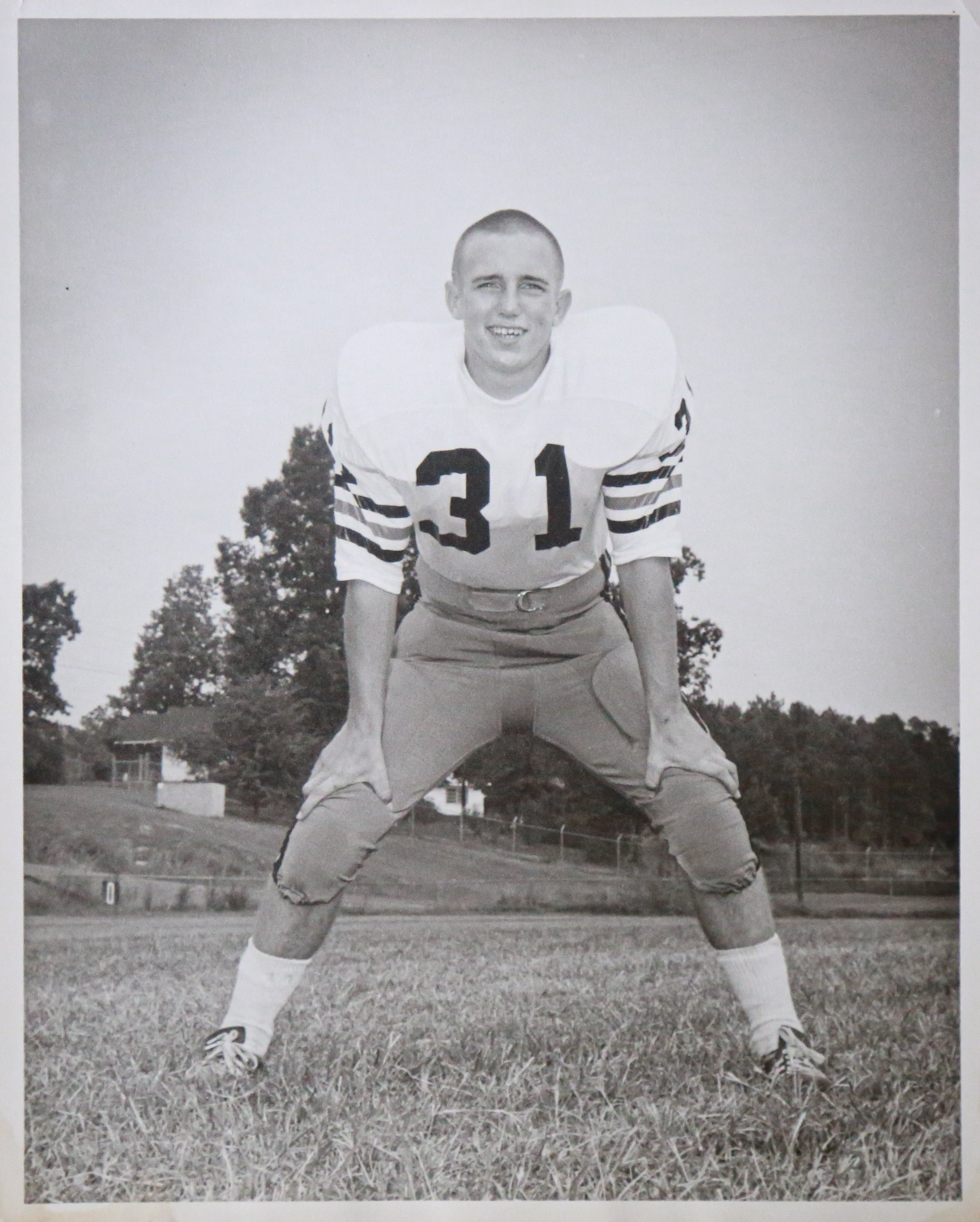

Food was scarce then, which contributed to Watts’ gaunt appearance. Rail-thin, he weighed 118 pounds his 8th grade year at Walker County High School. Then, a varsity football player named Gene Lawrence suggested Frank try out for the junior football team.

He points to an old photo of a scrawny teenage boy in a football helmet and uniform. “I was so proud of that helmet, I slept in it that night,” Watts admits. “I’d never had a uniform or been a part of anything.”

Then Frank, who was a Green Bay Packers fan, saw running back Jim Taylor lift weights on TV and started reading about weight training. “Mom and Dad got me a set of weights. I started eating better. I went from 118 to 145 pounds,” he says.

Frank later played fullback for Coach D. Joe Gambrell on the 1966 Walker County High School North-South All-Star team. “We had a play where I'd kick out the end,” Watts says. “The first thing to hit the ground was the back of their head—we didn't do that pushing stuff. I'd just lay them out.”

After high school, Watts "majored in football" at Troy State under Coach Bill Marsh. Tired of playing only during critical situations, he sat out a year before heading to the state of Louisiana to play for the Northwestern State Demons. “We played them at Troy. They were undefeated and won a national championship in Division 2A,” he says.

While taking a course at Walker College in the summer of 1968 to be eligible at Northwestern State, Frank spotted Pinkie in the cafeteria and swaggered over to chat. He admits it “took a while” to get a date because of his then-unsavory reputation.

“She and her friends were Christians and had a big impact on me,” Frank says. “To be honest, I thought I was dumber than dirt. I had horrible grades. I didn’t have nice clothes. The kids made fun of me. She gave me confidence and believed in me.”

Frank was plagued by health issues twice at Northwestern State. In one instance, a weeklong bout with nausea and vomiting led to an emergency appendectomy and hospitalization, his weight plummeting from 195 pounds to 165. Then he suffered a severe knee injury during a game and dragged himself off the field. “Back then, it was an insult if you could not carry yourself off the field,” Watts says.

After his knee exempted him from the military draft in 1969, Watts laid track for the St. Louis-San Francisco (now Burlington-Northern) Railroad. Pinkie had encouraged him to get his degree, so he enrolled at the University of Alabama, where he managed the weight room and started a power lifting team.

“You're looking at Alabama's first strength coach,” he says.

Frank went on to compete in several powerlifting competitions in the 70s and 80s. In a photo from a 1985 Jasper Mall exhibition, he stands in a semi-crouch, biceps straining to lift weights over his head. “That's around 700 pounds on that bar,” he says. “The most I ever benched was around 450. The best I ever squatted was 770.”

His name was recently added to the 2021 Alabama Power Lifting Hall of Fame.

Racial tension was rife in the 1970s when Watts was a teacher and coach at Minor High School. Watts vowed to show respect to each student, regardless of color, and earned their trust. He became close to his students and subsequently created a group for Christian athletes. “I’ve always had a heart for kids,” he says.

In the mid-80s, Watts accepted a position with a pharmaceutical company, thus beginning a long and prosperous career in that industry. An employer once asked him the secret to his success. “I said the greatest selling I ever did was to convince that redheaded woman to marry me,” he says.

It was Pinkie, he adds, who enabled him to witness to people. “I try every day, by the grace of God, to share the message of Christ,” he says. He taps a photo taken outside Talladega Federal Penitentiary. “I knew the guy in charge of the recreation area, and he invited us in. The prisoners all loved me.”

Through the years, Watts has undergone numerous surgeries on his back and shoulder. He is now battling recurring bladder cancer but says he doesn’t worry about it. “God has blessed me,” he says.

Surveying his various trophies, championship patches, and awards, Watts concludes the tour: “The thing that matters most is, how will people remember me? I hope that the memories I give them… will be good memories.”

A certain “redheaded woman” would undoubtedly agree. 78